The importance of the setting of ‘The Lagoon.’

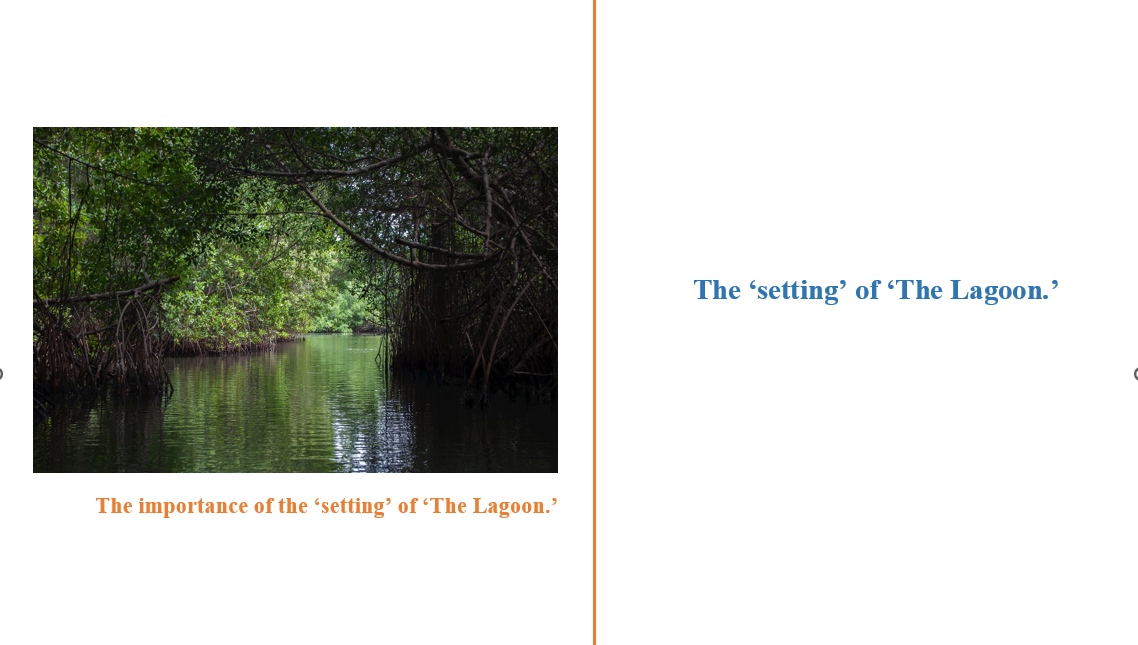

Arsat’s ‘clearing’ is ‘a wide sweep of a stagnant Lagoon’ which is distinguishable from the narrow stream and the dense forest that leads to this central arena. Actually, here the moral forces of human nature will compete with the imagined consequences of evil in a final showdown between Nature and Man, and Fate and man’s volition. Conrad’s use of topographic distinction is thematic; it formulates polar differences in human dispensations. Arsat’s ‘clearing’ like Emilia’s home in ‘Nostromo’, is the apparent hope and brightness in the midst of an enveloping gloom: –

‘The forests receded from the marshy bank, leaving a level strip of bright green, reedy grass to frame the reflected blueness of the sky.’

In contrast to the ‘bright green’ of the ‘marshy banks,’ ‘the glistening blackness’ of the creek water is overhung with ‘tracery of small ferns, black and dull, writhing and motionless.’ The twisted root of some tall tree entangles with the dark ‘tracery’ ‘like an arrested snake.’ The ‘snake’ image is evoked further in the metaphor of the canoe gliding from the river into the creek ‘like some slim and amphibious creature,’ and in the ‘tortuous’ contours of the creek. The snake in the Biblical Eden forebodes Evil and the white man is deemed to be in league with the Devil. To the native polers of the white man’s canoe, however, the dark-skinned Arsat is the embodiment of ‘the Father of Evil’ because he is a stranger who ‘repairs a ruined house’ and dwells in it.’ As the canoe bearing the White man draws closer to Arsat’s cabin, the close association of the ‘snake’ image and the atmosphere of evil involve (at a metaphorical level) the Whiteman with Arsat’s burden of guilt-later revealed as a product of his faithless betrayal of his brother to secure his selfish Romantic interests.

The Whiteman had known Arsat years ago, and helped him fight in times ‘in times of trouble and danger’. His liking for Arsat was evident as he occasionally passed nights with Arsat and Diamelen in their cabin on the lagoon during ‘his journeys up and down the river.’ The Whiteman’s liking for Arsat can be characterized as typically non-intrusive and convenient. His participation in Arsat’s confessions of evil and night-long expiatory suffering is mild and non-effusive. He feels sad and sympathizes with his Eastern friend but cannot do anything beyond offering to take him away from his lonely hut after Diamelen’s death. The night’s episode does not change the Whiteman’s course of action. In the morning he sets out on his journey. Although the mist lifts with the morning sun, growing brilliant and warmer upon Arsat’s clearing and the Whiteman resuming his journey. The final posture of Arsat remains mysteriously indecisive:

‘…he looked beyond the great light of cloudless day into the darkness of a world of illusions.’

The dark reality of the Malayan forests does not appear to connote an expiry of Arsat’s act of penance. He continues to be troubled by the darkness of his festering guilt. He announces wars on his brother’s killers because war and love are the two complementary passions that engender the tribe’s motto in life. But Arsat’s final attitude as he looks out fixedly at the heart of illusion appears to belie promises of the fulfillment of any such wish. He is entrapped in an existential reality.

Moreover, at the story’s close, the sun rises, the ‘whisper of unconscious life’ grows louder, and a white eagle soars magnificently into the sky. But this is an ironic contrast, for Arsat is left standing paralyzed, looking beyond the light and into a dark world of illusion. The way in which the light and dark motif works in “The Lagoon” suggests that, though Arsat achieves a degree of relief by telling his story to the Whiteman, he is merely substituting one illusion for another. Even if he goes back to avenge his brother, the return will be in no sense triumphant or act as an innate stupidity or maybe a defective moral sense.

Arsat’s life grows out of the mysterious atmosphere of water, forest, darkness, and mist. He lives in Nature and at the mercy of Nature without the benefit of medicine that may have saved Diamelen’s life. The hut he has rebuilt on the lagoon is made of reed that grows along the water’s edge. Every event of his exiled life is tinged by the natural sounds and colors of the eerie setting. Diamelen’s motionless and burning body lies covered in a red cloth, the color that signifies imminent death. Before the daylight over the forest vanishes, it changes into an ‘enormous conflagration,’ a ‘red brilliance,’ and then the ‘stealthy shadows’ rise like a ‘black and impalpable vapour above the treetop’. The light in the sampan moored afar shines with a ‘hazy red glow’ before dying out completely. Even the stars in the night-sky glitter in ‘vain’ against the thick, enveloping darkness.

So, to conclude we can say that Arsat’s journey from a make-believe world of passionate wish fulfillment to a forlorn state of disillusion reaches a watershed with the nightmarish end of Diamelen’s life. With Diamelen passing away in the wee hours of the morning, the dawn breaks ‘over the semicircle of the eastern horizon.’ This marks a symbolic change, from darkness to light; nowhere in the story has the sunshine been described so brilliantly as the end of the story. Perhaps, the realization of guilt and subsequent penitence is the enlightenment in Arsat’s life; he can stare at the sun and compare the state of revelation to the ‘darkness of a world of illusion.’

———————————

The Work Cited Page

1. Conrad, J. (2023) The lagoon. London: Penguin Books.

2. Ingersoll, E. (1988) Explores Journal- volume 66, p.